Independence Day, Or Was It?

July 4th, 1776

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania State House (Currently known as Independence Hall)

It was hot! The windows were closed for security reasons. The air condition wasn’t working! The fellows inside the assembly room were wearing what could be considered appropriate for an Alaskan winter!

Self-doubt! Distress! Fear! Apprehension!

Excitement! Exhilaration! Honor!

A myriad of emotions ran throughout the room as the secret they were keeping was about to get exposed. And then there was that other thing.

“We’re about to commit treason!”

“Okay gentlemen! Get those pens out! Get ready to sign! It’s going to be the most important document in American History!

“Tommy Jefferson worked on this thing down the street at the Graff House for almost two months!

“We’re all in agreement on this thing, right?” An uncertain pause hung over the room.

“RIGHT?”

“GUYS?”

An uneasy cloud surely hung over the room. Were they ALL in agreement? Probably not! But, peer pressure and a dose of, “if I don’t sign this thing, I’ll go down in history as … that guy!

But the coup de grâce to this whole independence thing was much simpler… they really didn’t have anything to sign!

The actual parchment paper had not even been selected. It would have to be printed on parchment, then brought secretly to the statehouse. Tomorrow? The next day? Next week?

Jiffy Printers at the mall didn’t exist! Not to mention the mall … Okay, we mentioned it.

This was 1776! Even Benjamin Franklin couldn’t print the thing that fast! And his office was just down the street.

What do we do? What will we do? (Recognition to Karl Malden—ask your parents …)

Maybe we all just agree that this is the right thing to do. Okay guys? Can we just do that?

Actually, they had already starting doing that. 2 days before! That’s right, we had another possible 4th of July, on the 2nd of July!

A draft of the document was presented on July 2nd, and for the next two days they continued to edit words and phrases, much to Jefferson’s annoyance. He had put up with that with Franklin and Adams for the last month at Graff House. Now he had probably 30 to 40 of the delegates to Congress messing with his baby! Which begs the question … where were the other 15 or so delegates?

And what about New York? They were the only ones left that had not given the “A” Okay for independence from Britian. That was more than a sticky problem. It needed to be ALL or NOBODY!

Hang on! So, what actually happened on the 4th of July?

All of the edits were finally agreed upon and the Second Continental Congress finally approved the wording of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. But a larger problem existed. Not everyone was there. New York was still hanging out with a well, maybe as the final state approval. And there was actually nothing to sign!

As Karl Malden would ask … (see above).

The Declaration of Independence wouldn’t mean much if no one knew about it. So, the boys got sneaky. Instead of signing a piece of paper that had the words, “THE UNANIMOUS DECLARATION OF THE THIRTEEN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA written on it, they decided to play with the words just a little.

IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776. A DECLARATION BY THE REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, IN GENERAL CONGRESS ASSEMBLED.

These were the words that the people would soon see as the Dunlap Broadside was quickly printed, not by Franklin, but by John Dunlap, another Philadelphia printer. 200 copies flew off the press and were distributed to state assemblies, conventions, committees, and councils of safety. It was also a good idea that several military commanding officers get in on the party.

So, with a change of wording, and the blatant omission of anyone’s name except John Hancock, President of the Congress, and his Secretary, Charles Thomson they were off to the races! And everyone was off the hook for treason … except Hancock and Thomson!

When New York finally approved it would go along with the Treasonous Experiment, it was July 19, 1776. A new printer was selected, Timothy Matlack, the clerk to Secretary of the Congress, Charles Thomson. But Tim had the dubious task of actually hand writing the document, including the words, UNANIMOUS DECLARATION. This would be the document actually signed by the members of Congress, on August 2nd, 1776. This was no longer Thomas Jefferson’s original document.

August 2nd, 1776

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania State House (Currently known as Independence Hall)

WHOO HOO!

The Big Day!

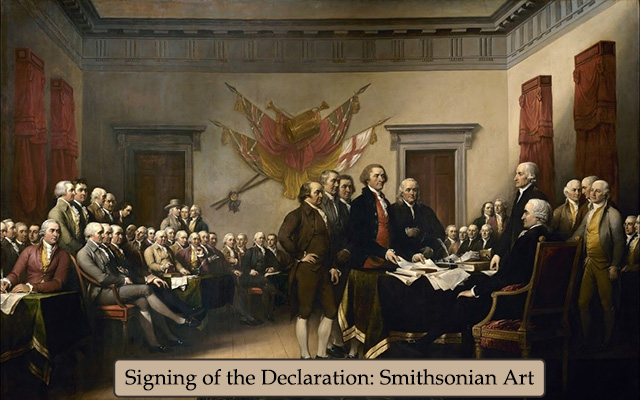

Nice painting! Only one problem. They are not in the official signing room!

If you look at the actual room photo in this blog, it is obvious the artist (unknown) had never been to the Philadelphia State House.

The door frames are wrong. There are too many windows. And, even Sherlock Holmes would be stumped by The Case of the Missing Candlelight Chandelier … did the disgruntled Jefferson take it as a souvenir?

On August 2, 1776, 49 delegates, not 56 signed the handwritten Matlack Parchment. It took the other seven delegates at least until November, or possibly even January of 1777 to sign. This was not unusual as those delegates slowly arrived in Philadelphia after their initial election, or possible re-election to the Continental Congress. And then there was Thomas McKean.

A representative from Delaware at the First and Second Continental Congress, McKean was also in the military and served alongside George Washington. He was also the President of the Continental Congress in 1781 presiding during the battle and British surrender at Yorktown.

Although he was one of the delegates to approve the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, he was forced to leave Philadelphia before it was officially signed on August 2nd. His reason was admirable. He rejoined the Fourth Battalion of the Pennsylvania Associators as Colonel in command. This put him in charge of the militia unit created by Benjamin Franklin in 1747.This also kept him out of the August 2nd Declaration final signing ceremony.

Historians have no definitive proof of when McKean actually signed; possibly in January 1777, or as late as 1781!

As his signature does not appear on the January 17, 1777 authenticated printed copy of the Declaration of Independence, he obviously signed after that date.

The Declaration was finally delivered to Great Britain for the King’s reading pleasure in November of 1776.

Anyway

Happy August 2, 1776!

Saving Liberty